Book Review

Tom Stuart-Smith has deservedly earned recognition as one of the great British garden and landscape designers. His reimagining of the box parterre in the walled garden at Broughton Grange where the hedging was organised not in a traditional geometric layout but following the cell pattern of a leaf as viewed under the microscope brought him to the attention of the gardening media. Of course, his eight gold medal winning gardens at the Royal Horticultural Society’s Chelsea Flower Show with three awarded the coveted Best in Show award brought international fame and recognition. He was commissioned to design the replanting of the vast formal Italianate gardens at Trentham and startled the horticultural world with a style that “was consciously opposed to anything that Barry (Sir Charles Barry, architect) and Nesfield (William Andrews Nesfield, landscape designer) would have approved of. In recent years he developed the masterplan for the 154-acre Royal Horticultural Society’s new garden, Bridgewater, in Salford, Greater Manchester, which opened in May of this year.

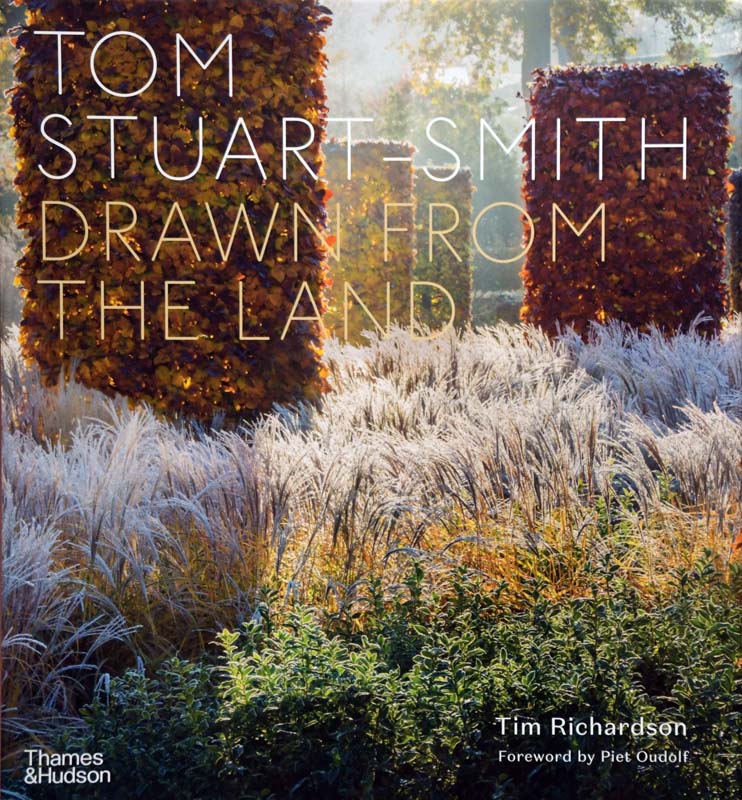

These are just some of the more well-known highlights of Tom Stuart-Smith’s career but enough to whet anybody’s appetite to read more of his design projects and this book will serve that purpose to perfection. The publishers, Thames & Hudson, deserve the greatest praise for their inspired choice of author, Tim Richardson, to document Tom Stuart-Smith’s work for when you bring great people together the results can be, as with this book, particularly special.

Retrospective accounts or assessments of a designer’s work may have the value of hindsight but a contemporary discussion between designer and author is far more open, insightful, informative and interesting and this book is certainly a perfect example of the success of such an approach. Designer and author each contributes two essays to the book: Tim Richardson writes on “Planting” and “Design Philosophy” while Tom Stuart-Smith contributes “Close Encounters and the View from Above” and “Attachment, Separation and Loss, A Garden Narrative” while the twenty four garden projects described are obviously a collaborative effort.

The accounts of the garden projects are organised into groups of four or five, interspersed with the four essays which provide a change of pace for the reader, an excellent way to organise the material of the book as an uninterrupted reading of twenty four garden descriptions, despite how excellent they are, might be tedious. As organised here, it makes for a very pleasant read and, I should add, it is a read which is lavishly illustrated with the most excellent photography so the whole is a triumph of content, style and presentation. Yes, you may gather, I really and truly enjoyed the book.

I found the insight given to the mindset of the designer, his design philosophy, very interesting. For Tom Stuart-Smith the big picture is most important, the overall effect, how the garden fits with its setting and, possibly, historic background and planting is only seen as the final element, the icing on the cake, so to speak adding value and spontaneity. His planting style is discussed and described and could be said to fit with the New European Perennial Movement though with a British flavour. European designers are inclined to use a narrow selection of outstanding plants repeatedly in whatever garden project they design. Such a narrow range does not fit with British garden culture where there is a greater desire for a broader range of plant, where innovation is expected and even demanded. Tom Stuart-Smith has what he calls his “float plants”, the central and almost constant selection which he uses repeatedly, but these are augmented and supplemented with a selection which boosts interest and makes each planting individual and distinctive.

The discussion on whose garden it is when a project is completed was interesting: was it the garden of the owner or of the designer. The balance of ownership, it seemed to me, swung to one or the other depending on the involvement of the project commissioner – the more they were keen on gardening, the more it became their garden and less that of the creator but all gardens change and what the designer has created may well change considerably over the years which explains why Tom Stuart-Smith regularly includes a void – a central pond, for example – in his designs for that will most likely never change and will remain forever his!

Perhaps it was diplomacy which left some questions unanswered, even unmentioned. I wished for a reaction to the significant changes made to the work on part of the Windsor Castle grounds. The redesign had involved moving a carpark from where it was visually intrusive to allow for more planting but, it would seem, those who use the carpark regularly couldn’t endure the extra few minutes’ walk from the new location so it was reinstated. Similarly, I wondered what his reaction was when a garden he created was not well maintained in the years following its development. I imagine it must be at least annoying if not downright galling but there was no mention of such events though I’m sure it must occur. I’m sure Tom Stuart-Smith is far too gentlemanly to refer to such things but a full and complete account of his work might mention them, I feel.

Finally, a short quotation which expressed something I had felt, while visiting Rousham, but which Tom Stuart-Smith pens perfectly. He was writing of Rousham and of The Garden of the Running Footman at St. Paul’s Walden Bury and said that both have “that distinct quality of separateness which makes us as visitors feel we are in some way secondary to the pulse of the place itself.” When I read those words, I felt I had shared a feeling with the author and it gave a little peep inside his mind

Rousham was beyond me. I couldn’t understand nor grasp how a garden could lead me so gently and unobtrusively around the space so that I went without ever making a decision on direction or choice on where I wished to go, that I went along following a route which always felt the natural and obvious way to go. While I felt I had wandered aimlessly, I later realised I had all the time been gently guided by the genius of the garden’s creator – William Kent – and I feel grateful such genius continues to this day.

As one would say, “Read all about it” – and I’m sure you will enjoy it!

[Tom Stuart-Smith: Drawn From The Land, Tim Richardson, Thames & Hudson, London, 2021, Hardback, 320 pages, £50, ISBN: 978-0-500-02231-3]